May 9 – 15 is SAMSHA National Prevention Week when local, state, and national allies promote substance abuse education and prevention. The efforts come on the heels of the latest CDC finding of more than 87,000 drug overdose deaths in the 12 month period ending September 2020. The grim statistic topples the number of U.S. military war dead in all American wars since World War II.

The leading causes of drug overdose deaths were manufactured fentanyl and other synthetic opioids trafficked from China and Mexico, followed by toxic cocktails of heroin spiked with manufactured fentanyl, methamphetamine, cocaine, and other psychostimulants.

The potency and affordability of these drugs is reported in the DEA’s latest Drug Threat Assessment. Fentanyl, 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine, and Carfentanil, an elephant tranquilizer that is 10,000 times more potent than morphine, can be purchased on the street for less than $10.

Before fentanyl, from 1960s to 1990s, street drugs were sold and ingested in grams. It was common for people to use 1-3 grams of heroin a day without overdosing or dying. Now opioids like fentanyl and carfentanil, due to their extreme potency, are sold and used in micrograms. One microgram is one-millionth of a gram. People are dying using 2 to 5 micrograms of fentanyl that cost $5.

Covid’s role in spiking the death toll, the highest since the first wave of opioid-related deaths in the 1990s, is indisputable. Essential residential and outpatient treatment services and support programs, critical to those battling addiction and relapse, began to fall apart during the early months of the pandemic and at the height of the lockdown. Services and programs were scaled back or retracted completely. In-person groups such as AA and NA went virtual or disbanded, sending many into isolation and relapse.

Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) clinics that normally dispensed methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone to hundreds of patients on a daily basis; and physicians offices that prescribed the medications, reduced operating hours during the pandemic, placing those most vulnerable to relapse at risk. Covid-related adverse stressors due to job furlough, unemployment, financial and housing insecurity, also played a role in increasing addiction and relapse.

While the drug overdose death toll of 87,000 is eclipsed by Covid’s half a million dead, and dulled by various other morbidity and mortality data from gun deaths to obesity, it resonates specifically with those on the frontlines and trenches of the opioid epidemic. Grieving families, those grappling with addiction and their loved ones, addiction treatment providers, and the recovery community are reckoning with, and reeling from, the staggering number.

Obituaries, tributes, and memorials written by grieving families in the public domain, and news reports featuring them, narrate their loved ones’ battles with addiction. Keyword searches on these platforms for “drug overdose,” “heroin,” “fentanyl” and “opioids” retrieve painful accounts of those who lost their lives to opioid overdoses.

Obituary writers chronicle sudden and gradual milestones of opioid addiction that afflicted their relatives, that began with recreational use and ended in their deaths. They narrate the Sisyphean efforts of those attempting to overcome their addiction for months, years, and decades, and the brief reprieves of abstinence that gave them hope. Some mentioned the pain their loved ones endured as they wrestled with addiction and struggled to live. Some wrote about their loved ones’ regrets over addiction robbing them of major milestones— college, careers, marriage, and children.

Parents talked about the descent of their loved ones into crime, homelessness, and mental illness. Many of the afflicted were estranged from their families at the time of their death. Some died after leaving treatment, in halfway houses, at home, in motels, in public places, sometimes alone. Frequently, the bereaved expressed relief and gratitude that their loved ones were no longer suffering and had found the peace that eluded them in their lifetime.

In their unflinching honesty, some families wrote about the exhausting efforts to keep their children, spouses, and siblings alive, project-managing their loved ones’ treatment, and accompanying their loved ones through the highs and lows of recovery and relapse. Many have been traumatized. One woman wrote about performing CPR on her brother who had overdosed from meth and fentanyl, as her screaming parents and her two young children watched in horror. “I knew he was dead five minutes after I started CPR. But I wanted to try to save their son, their uncle.” Another woman wrote about losing her mother to fentanyl, two brothers to heroin, and a nephew to opioids, and what she feared most—the dreaded call about another nephew now addicted to heroin and homeless on the street. “I live with guilt that I could not save my family,” she wrote.

The final tributes reveal the complexity of opioid addiction, the psychology of those who suffer from the chronic disease, and the dimensions and reach of it that make it a family disease that spares no one in a family unit.

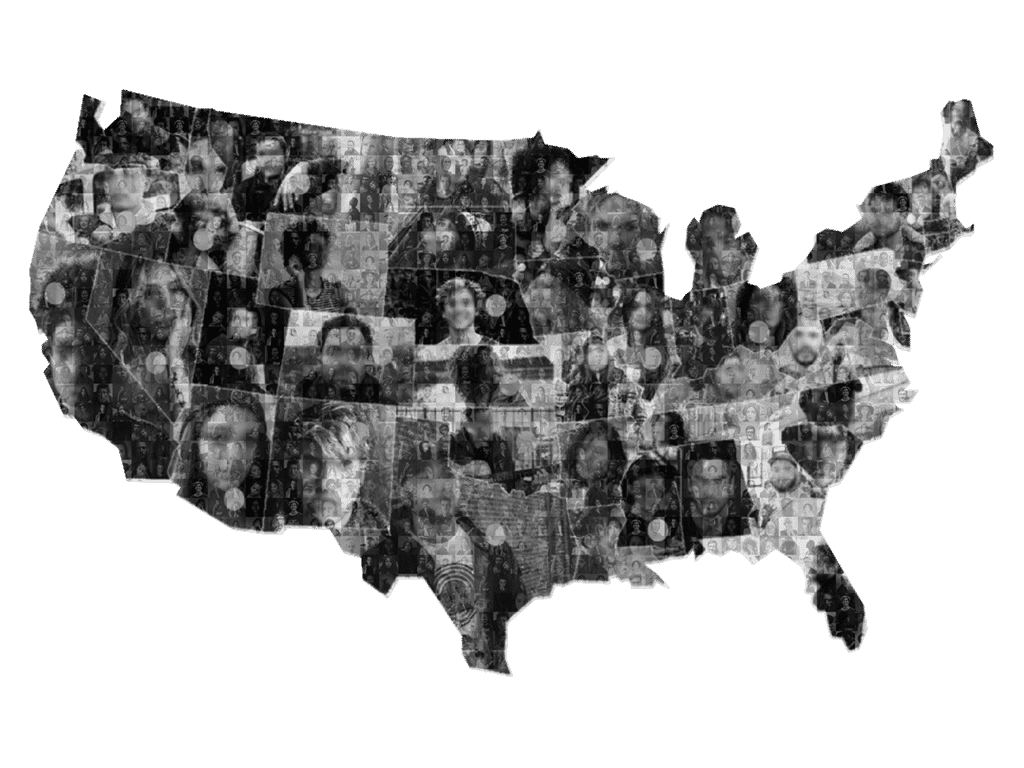

Each of the following elegies and laments, paraphrased for brevity, stands for the 87,000 other lives lost to opioid addiction in 2020. Taken together, they form a mosaic of irreplaceable, incalculable, irretrievable loss.

“Our son could have been anyone’s son. Our child could have been anyone’s child. He was ours and we loved him.”

1 of 26“By warning of the dangers of heroin and Fentanyl, we hope for his death to have some meaning.”

2 of 26“She fought a courageous battle with addiction before her overdose.”

3 of 26“We never gave up on him. We did everything humanly possible.”

4 of 26“He died of a drug overdose just like so many of his friends.”

5 of 26“We share his story in the hope that his death can help someone, that his life was not wasted, that he did not die in vain. “

6 of 26“The disease of opioid addiction killed him and shattered our lives. “

7 of 26“We cannot imagine how we will endure the pain of losing her. “

8 of 26“We cannot imagine how we will endure the pain of losing her. “

9 of 26“To all the young people doing fentanyl and heroin who think this won’t happen to you. It will. Please get help. “

10 of 26“If your child is using, please don’t judge, be kind, support them through treatment and recovery. “

11 of 26“The disease was more powerful than he was. “

12 of 26“He struggled with addiction for years. He was fine for a year, he thought he had beat it, but it got him.”

13 of 26“She was only 25. “

14 of 26“Nine months sober, fourteen days out of rehab, and he died of a drug overdose.”

15 of 26“He died the same way thousands of others have, of a drug overdose. “

16 of 26“He was one of a kind. We will do what we can to help others in his memory. “

17 of 26“She struggled but continued to strive for a life free from addiction. “

18 of 26“He kept trying and relapsing and trying until the last fatal overdose.”

19 of 26“He fought like a hero to save his life until the end.”

20 of 26“He battled depression and addiction and died of a drug overdose.”

21 of 26“He was a victim of the heroin epidemic and died from it.”

22 of 26“She was my only child.”

23 of 26“We share his story, in case his death can help someone.”

24 of 26“His was a senseless death from a crippling disease.”

25 of 26“He was in recovery, actively working to stay in recovery before an accidental overdose.”

26 of 26Illustration using Stock Photography

Many families of those who died of drug overdoses railed against the lack of affordable, available, effective treatment for their loved ones. They revealed the last months of their loved ones’ lives as hyperactive cycles of addiction, abstinence, and relapse. Some cited their loved one’s active participation in recovery, counseling, and support group meetings. None cited using overdose reversal medication to revive their family member. None cited their loved ones’ participation in medication-assisted treatment protocols or harm reduction programs.

These omissions suggest that those suffering from opioid use disorders, and their families, need information and access to overdose reversal medication and evidence-based addiction treatment.

During an overdose, the brain and body are flooded with very potent opioids that give the user an explosive “high.” The user’s breathing slows down, heart rate decreases, and alertness fades. The brain is deprived of oxygen during this dangerous period of decreased breathing and heart rate. The user will quickly go into cardiac arrest, brain damage, and death due to respiratory malfunction.

But opioid drug overdoses, if caught in time, can be prevented with drug overdose reversal medication. Naloxone (traded as Narcan or Evzio) is an antagonist that binds to opioid receptors and blocks or reverses the effects of other opioids. When given in time, it can quickly restore and normalize breathing and heart rate. FDA-approved Naloxone is available in three formulas. The first is an injectable that requires training and assembly. It is intimidating for non-medical professionals with no experience, or who feel nervous giving injections.

The less intimidating iteration is Evzio, an auto-injection that is already filled with Naloxone. When activated, the device provides audio instructions to those offering aid on how to deliver the medication, similar to auto-defibrillators. The injection is administered to the outer thigh area. The most user-friendly Naloxone for those with no medical training, who are nervous about injections, is the Narcan nasal spray that is sprayed into one nostril while the opioid user is lying on his/her back.

Naloxone saves lives. Yet, one 2017 study found only 2% of opioid users at high risk for relapse and addiction filled prescriptions for Naloxone. Easy access to Naloxone at an affordable price or free should be the goal and norm.

Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) is an evolution in addiction science, a holistic treatment model component, and the gold standard in treatment for opioid use disorders. Where conventional paradigms in treatment focus on abstinence, catharsis therapy, health and wellness, and support groups such as AA and NA, MAT is a disease management model that strives first for patient stability through medication assistance, then as a launchpad for recovery, and finally as an integral tool in a comprehensive treatment plan unique to each individual.

MAT is an evidence-based, next-generation addiction treatment that meets the most immediate and urgent needs of those suffering from opioid use disorders, by first allowing detoxification, and then stabilizing patients during transitory periods. An MAT protocol regulates brain chemistry and biological functions, relieves the symptoms of withdrawal from opioids, diminishes cravings, and improves a person’s ability to function normally.

A custom-designed treatment plan that includes MAT, psycho-social support, and behavioral health modules enables those who suffer from Opioid Use Disorders (OUD) to stay engaged in programs for the long term, significantly lowers a return to opioid use, increases immunity against relapse and overdose, and substantially increases the odds of sustained recovery.

When added to the arsenal of conventional treatment and wraparound support services, MAT is an exemplar in care for opioid use disorders. It has the capacity to address the chronic disease according to each patient’s needs. Several studies show that MAT reduces the likelihood of relapse and overdose fatality significantly.

The three FDA approved MAT drugs for heroin and opioid dependency are Buprenorphine, Methadone, and Neltraxone.

Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist, that at low to moderate rates mimics similar but low grade effects of opioids such as euphoria or respiratory depression. It also blocks the effects of other substances. Since it is a long acting agent, it allows patients to have intervals in regimen. It diminishes withdrawal symptoms and cravings, and lowers the risk of misuse and danger of overdose. It is prescribed as a tablet, cheek patch, or six-month implant under the skin. It is prescribed in doctor’s office after screening and evaluation.

Methadone is a synthetic full opioid agonist that activates the same receptors in the brain that other opioids such as heroin and morphine do, but at a slower pace. It does not produce euphoria, but does reduce opioid craving and withdrawal and blocks the effects of opioids. It is a long lasting agent, taken once a day, and is available as liquid, powder, and tablets. Methadone is only dispensed in specialized treatment programs and clinics.

Naltrexone is an opioid antagonist that prevents the effects of heroin, opioids, and alcohol on the brain by blocking opioid receptors. It is non-addictive, does not mimic the effects of other opioids, and prevents full relapse or overdose by other drugs because of its antagonist properties. The earlier pill form has been replaced by an extended-release monthly injectable, Vivitrol, which has proven effective in MAT. While Naltrexone is not as effective for heroin and opioid treatment alone, in combination with buprenorphine it is an effective treatment. Its use for successful treatment is supported by multiple scientific studies.

Multiple medical and health authorities including the American Medical Association (AMA), American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry (AAAP), the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM), National Institute of Health (NIH), and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), have declared their support of MAT and the removal of barriers to MAT for use in addiction treatment plans.

Yet, despite substantial evidence that MAT is effective, the notion that MAT is a poor alternative to full recovery is prevalent among those trying to battle the disease, their families, healthcare providers, and the recovery community. MAT is routinely maligned as “replacing one drug with another, one addiction with another” and that the best outcome depends on abstinence, or in the recovery parlance “staying clean.” Conversely, medication to manage addiction is viewed as inauthentic recovery and frequently stigmatized.

To make MAT readily available to those suffering from opioid use disorders who need it, it needs to be affordable, covered by insurance, and offered by healthcare providers. It requires the entire addiction treatment field to integrate MAT into treatment philosophy and practice.

Two recent studies show the low integration and use of MAT in addiction treatment.

In a July 2020 study, cited in JAMA Network, of 2800+ residential treatment centers nationwide, 1680 of them did not offer any MAT and only 36 offered all three MAT protocols—naltrexone, buprenorphine, and methadone. Just 34,000 of the 232,000 patients received MAT as part of their primary care while in residential treatment.

In another 2020 ‘secret shopper’ phone survey by JAMA, of 368 residential treatment centers nationwide, only 106 offered MAT as part of primary care treatment, while 114 offered MAT for detoxification to patients who Initially entered treatment.

One hurdle to universal adoption of MAT includes the qualifying criteria for physician waivers to prescribe some MAT and the restrictions to dispensing them. Methadone can only be prescribed in daily doses by licensed opioid treatment programs, while physicians need special training and waivers to prescribe buprenorphine.

Another barrier to wider availability of MAT is the cost of medications, insurance coverage, and out-of-pocket affordability. The National Institute of Health surveyed the cost of MAT in certified opioid treatment programs. It found: Buprenorphine with twice-weekly visits cost $115 per week or $5980 per year; Methadone with daily visits and psychosocial and medical support services cost $126 per week or $6552 per year; and Naltrexone with related services cost $1176 per month or $14,112 per year.

The cost of MAT is small compared to the cost of opioid addiction to individuals, families, community, and society, which has been estimated at $78 billion which calculates the cost of incarceration, homelessness, transmission of diseases, drug overdoses, drug-related injuries, lost productivity, and treating babies with opioid dependency.

MAT, when used as part of a customized full-spectrum treatment regimen that includes behavioral therapy and social support, offers the best outcomes for people suffering from opioid addiction. It is the gold standard in the arsenal of addiction treatment for those suffering from opioid and substance use disorders and has been shown to significantly reduce and prevent drug overdose deaths.

According to the American Society of Addiction Medicine, patients who receive drug maintenance therapy are 75% less likely to die from their addiction compared to those who do not receive those medications. MAT when combined with psycho-social treatment modalities shows it can make a difference in stopping the loss in drug overdose deaths.

For a review of New Leaf Detox and Treatment various programs including MAT, please visit: https://nldetox.com/about-us/

https://nldetox.com/san-juan-capistrano-medication-assisted-treatment/

For more information contact (949) 822-8664

New Leaf Communications

At New Leaf Detox & Treatment

https://nldetox.com/

For more information contact newsroom@nldetox.com

Start Addiction Recovery at New Leaf Detox & Treatment's Detox Center In Southern California

Send us your information and receive a free verification of benefits. All submitted forms or phone calls are completely confidential.

Contact Us